The life of L. L. Nunn |

Search tip: You can do a keyword search of this file by using the Edit-> Find in Page (Ctrl+F) feature on your Web browser.

L. L. Nunn timeline

|

1853 Mar. 16 |

Medina, Ohio |

Lucien Lucius born to Miriam and Charles Robert Nunn |

|

1865 |

Peru, Ohio |

Nunn family moves to another farm |

|

1866 |

Oberlin, Ohio |

Nunn meets and is profoundly influenced by revivalist preacher Charles G. Finney |

|

1867 |

Oberlin, Ohio |

Nunn begins studies at Cleveland Academy under Linda T. Guilford |

|

1869 |

Oberlin, Ohio |

In business with oldest brother Fred, including the cultivation of bees for honey |

|

1873 fall |

|

Travels to London with Fred |

|

1874 |

Oberlin, Ohio |

Fred dies |

|

1876 fall |

|

Travels to Germany to recuperate after financial troubles |

|

1877 fall |

Boston, Mass. |

Nunn begins working in the law office of Henry W. Paine |

|

1878 fall |

Boston, Mass. |

Nunn enters Harvard Law School |

|

1879 summer |

Peru, Ohio |

Works at family farm |

|

1879 fall/winter |

St. Louis, Mo. |

Studies extensively in public library |

|

1880 spring |

Leadville, Colo. |

Nunn moves west, opens Leadville Restaurant |

|

1880 |

Leadville, Colo. |

Opens a more upscale restaurant, The Pacific Grotto |

|

1880 Nov. |

Leadville, Colo. |

Leaves town with partner Malachi Kinney after the failure of Pacific Grotto |

|

1880 |

Durango, Colo. |

Opens new Pacific Grotto, enters the real estate business with Kinney and Tom Hall as Hall, Nunn, and Kinney |

|

1881 spring |

Durango, Colo. |

Closes businesses and walks to Telluride with Kinney |

|

1881 |

Telluride, Colo. |

Begins working in construction and carpentry |

|

1881 winter |

Telluride, Colo. |

Contracts typhoid fever; with Kinney, builds first bathtub in Telluride |

|

1881 |

Telluride, Colo. |

Organizes the Ilium Gold Mining Company, builds ten-stamp mill at Ophir |

|

1882 |

Telluride, Colo. |

Opens law practice under the name of Nunn & Kinney, begins developing real estate |

|

1882 |

Delta, Colo. |

Develops homestead and begins cattle ranching |

|

1887 |

Telluride, Colo. |

Partnership dissolved as Kinney leaves for Salt Lake City |

|

1888 |

Telluride, Colo. |

Nunn acquires controlling interest in the San Miguel Valley Bank |

|

1881 |

Ophir, Colo. |

Becomes manager for the Gold King mining interests and unites business interests under the name “Office of L. L. Nunn”; San Miguel Gold Placers Company organized |

|

1889 Sept. |

Telluride, Colo. |

Hires Stephen Bailey as secretary |

|

1889 winter |

|

Travels through England and the Eastern U.S. on legal business |

|

1890 summer |

Ames, Colo. |

Electrical

generator and motor received from the Westinghouse Company, installed in

the winter; Nunn makes Paul N. chief engineer of the Telluride Power

Company |

|

1890 winter |

Ames, Colo. |

First commercial long-distance power-transmission plant built (begins operations early 1891) |

|

1890 |

Telluride, Colo. |

Nunn organizes First National Bank of Telluride |

|

1890 Nov. 20 |

Telluride, Colo. |

San Miguel Consolidated Gold Mining Company incorporated (official date of incorporation Feb. 7, 1891), succeeds San Miguel Gold Placers Company |

|

1890 |

Telluride, Colo. |

Rio Grande Southern Railroad built, Nunn sells (??) in construction company |

|

1891 Feb. 13 |

Boston, Mass. |

First meeting of the Board of Directors of SMCGC; Nunn elected General Manager |

|

1891 |

Bear Creek Mill, Colo. |

Instruction begins for first student class of Telluride Institute |

|

1891 June |

Ames, Colo. |

Plant begins regular functioning work |

|

1891 Oct. 6 |

Telluride, Colo. |

Nunn acts as chairman for first annual meeting of the SMCGCS |

|

1891 Oct. 6 |

Telluride, Colo. |

Original power transmission line extended from Ames to Telluride |

|

1892 spring |

Telluride, Colo. |

Nunn builds 120-stamp mill on Bear Creek |

|

1892 summer |

|

Travels to Europe with Stephen Bailey |

|

1895 |

Ames, Colo. |

Experimental line constructed from Ames Station to Gold King Mill to test higher-transmission line voltages |

|

1895 |

Logan, Utah |

Buys the Hercules electric plant on the Logan River |

|

1896 Feb. 15 |

|

San Miguel Consolidated Gold Mining Company becomes the Telluride Power Transmission Company |

|

1896 |

|

Transmission system is converted to three-phase, with induction motors replacing synchronous ones |

|

1897 Feb. 11 |

Denver, Colo. |

P.N.’s daughter dies of measles and other complications |

|

1897 Aug. 8 |

Telluride? |

P.N. and wife move to Provo |

|

1897 |

Provo, Utah |

Builds Nunn’s Station, first power installation in the Provo Canyon |

|

1898 Feb. |

Provo, Utah |

Olmsted Power Station begins operations |

|

1900 |

Norris, Mont. |

Nunn builds plant on Madison River |

|

1900 |

Ophir, Colo. |

New powerhouse constructed at Ilium |

|

1902 |

Ontario, Canada |

With Paul, builds hydroelectric station at Niagara Falls for Ontario Power Company |

|

1903 |

Logan, Utah |

Logan Power Company absorbed into the Telluride Power Company |

|

1903 |

Nellie Mine, Colo. |

Miners’ strike |

|

1904 |

Provo, Utah |

Telluride Institute is expanded to the Olmsted Station |

|

1907 |

Grace, Idaho |

Builds power plant as part of the Bear River system |

|

1907 |

Chihuahua, Mexico |

Builds plant on the Fuerte River for the Lluvia de Oro Mining Company |

|

1909 Feb. |

Granville, Michigan |

Niece Florence dies |

|

1909 |

Ithaca, N.Y. |

Telluride House built at Cornell (opens in 1910) |

|

1909 |

Ophir, Colo. |

Ilium plant destroyed in flood |

|

1909 |

Telluride, Colo. |

|

|

1910 |

Ithaca, N.Y. |

Builds Telluride House at Cornell University, installs first students in fall |

|

1910 Sept. |

Telluride, Colo. |

|

|

1910 Nov. |

Chicago, Ill. |

Nunn is diagnosed with tuberculosis |

|

1911 |

Olmsted, Utah |

Signs constitution of Telluride Association along with 87 employees of the Telluride Institute |

|

1912 May 23 |

Bear Creek Mill, Colo. |

Fire shuts down operations at mill |

|

1912 summer |

|

Telluride Power Company taken over by the Electric Bond and Share Company of New York; Telluride Association split from the power company |

|

1913 March 12 |

|

Western Colorado Power Company organized, takes over Telluride Power Transmission Company |

|

1916 |

Claremont, Virginia |

Nunn attempts unsuccessfully to fund another school |

|

1916 Sept. |

Deep Springs, Calif. |

Purchases property to build Deep Springs School |

|

1919 |

Teague, Texas |

Sells diesel plant |

|

1923 |

Casper, Wyo. |

Sells diesel power company |

|

1925 April 2 |

Los Angeles, Calif. |

Nunn dies at the age of 72 |

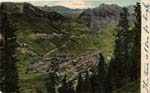

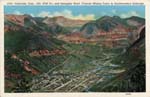

Views of areas where Nunn worked in Southwest Colorado:

Items

of interest in the Western Colorado Power Company business correspondence:

1) Telegram codebook of the “Institute” club, kept by Frank R. Sherwin, September 1890 – Box 2, Folder 1

2) Survey reports on “Stairs Water Power,” made by R. M. Jones, 1893 – Box 3, Folder 42

3) Newspaper articles: “A Beach Resort Monopoly – Garfield Surrenders to the Big Pavilion,” “British Light Syndicate in Salt Lake compels the public to get on its knees and beg for service,” “Here to Build a Plant – Mr. Boettcher promises competition in Light,” “Water eats Gold – millions in the Yellow metal recovered by Percolation,” 1895 – Box 6, Folder 10

4) Map of grants made by Governors Nichols and Dongan to the freeholders of Upper Manhattan Island, 1895 – Box 6, Folder 43

5) Diagram of tension work apparatus, 5 May 1896 – Box 9, Folder 27

6) L. L. Nunn’s correspondence notes, circa 1896-1899 – Box 9, Folder 42

7) Salt Lake City newspaper articles: “To use Draper Canal: City Water Turned into East Jordan Waterway,” “Jordan Water Fizzle: City’s Share No Longer Runs in Draper Ditch,” “Jordan Water Meeting: Another Conference Held in Mayor’s Office,” October 1899 – Box 13, Folder 42

8) Report on Waggoner ditch, 1900? – Box 17, Folder 16

9) Diagrams of Ames transformers, 1900 – Box 17, Folder 49

10) Daily work reports of construction done on Lake Hope and Ilium power lines, November 1900 – Box 18, Folder 1

11) List of electrical supplies at Provo station, 9 August 1900 – Box 18, Folder 2

12) Questionnaire for Pinhead occupational/educational placement, 1901 – Box 21, Folder 19

13) Notes of negotiations for sale of Camp Bird power, 4 August 1902 – Box 23, Folder 10

14) Survey of Bear Creek pipeline and adjacent properties, by H. C. Lay, 18 June 1903 – Box 24, Folder 33

15) Rough diagram of Trout Lake reservoir, 1904? – Box 25, Folder 1

16) Report on the Nellie Mine fire of January 6, 1905, with diagrams of wiring arrangement of Nellie Mine, report of operations for December 1904, San Miguel Examiner article of January 9: “Bad Blaze at the Nellie: Mine Building a Complete Loss By Fire,” January 1906 – Box 25, Folder 1

17) Senate bill no. 370, “an act to amend Sections 1 and 3 of an act entitled ‘an act concerning water rights’” – Box 26, Folder 35

18) Blueprints for Lake Fork pipelines, 1910 – Box 27, Folder 4

Self-representation

of L. L. Nunn as noted in his business correspondence:

An evaluation by Christine Ro, Telluride Association Intern at the Center

of Southwest Studies, July-August 2003

It’s difficult to tell whether Nunn was as genuinely generous as he appears in his letters (he writes of shouldering the medical expenses for numerous unrelated people, for instance), or whether, as Sweeting suggests, he was always intensely aware that in writing he was creating his own historical record. How aware was he that his actions and correspondence would be examined by future generations? Is it unfairly cynical to question his motivations?

The correspondence is full of requests for help, whether financial, occupational, or otherwise. And even with those pleas for money that apparently went unanswered, Nunn was still very openhanded with his funds as well as his attentions, to the extent that such liberality began to take a personal toll. In a letter to A.M. Wrench dated April 12, 1895, for instance, he writes, “I have been so driven to desperation by my sick and lonely condition, and the ever increasing demands made upon me that I begin to hope that the suffering has rought [sic] its own cure. I am here careing [sic] for three invalids, Mrs. Whitman, Fred and Urban. If I had a companion with me who could assist me in attending to business matters, which I cannot neglect, I would feel strong but I am alone and have to be alone except as I am with the sick.”[i] Similarly, while discussing a Miss Kibbe in a November 18, 1899 letter, he complains that “Every affair of the kind is a burden to me, and I feel that the Hospital would not be a bad place for me to go to. However, I have no intention of throwing off the responsibilities that seem plainly to be put upon me.”[ii]

It’s hard not to admire the evident generosity behind such statements, or the sense of social obligation obvious when Nunn refers, in a January 19, 1901 letter, to “the difficulties of winter construction,” but notes that the company’s customers depend upon the power station being built: “Our failure to serve them would interrupt the employment of 4,000 men and a product of over $20,000 per day.”[iii] Even the seemingly mundane correspondence reveals a commendable sense of charity, as in the bills, telegrams, and receipts from the Keeley Institute of Chicago,[iv] where Nunn paid for the rest cures or addiction rehabilitation of at least four people.

Nunn, then, was clearly a bighearted man. The complication is that he was also ideally situated for self-representation, and it isn’t obvious where the line between Nunn the private altruist and Nunn the public philanthropist lies. For not only in the correspondence, of which even the most trivial of telegrams, rate statements, bills, etc. he apparently retained, but in the contemporary media, which seemed to have a fascination with him and other important mining figures, Nunn could fairly assume that a record of his deeds and words would be kept.

And indeed, even in the late 19th century, Nunn must have been acutely aware of the power of the media to influence his business dealings and public reception. Besides owning a newspaper himself, he used the forum to advance business propositions, as in a letter published in The Telluride Journal, dated June 15, 1891 and addressed “to the citizens of Telluride,” in which he advocates the construction of a local hotel. While attempting to foster a sense of community (he includes himself in the town’s “us”), Nunn writes that “my only desire in the matter is to advance the general prosperity of the town.”[v] Likewise, a March 18, 1892 letter to the editor of the Journal, printed in his own newspaper, the rival Telluride Republican, declares, “No one knows better than you do the vast benefit which the work which I have done in this county has been to the entire community. Admissions on this score have been wrung from my opponents.”[vi] Nunn clearly understood the means and potential of manipulating public opinion.

Reciprocally, the newspapers loved him. The Telluride Journal declares on July 18, 1891 that “to Mr. L.L. Nunn, general manager of the Gold King Property, is due the credit for the inception and successful demonstration of this enterprise,”[vii] and refers to him on June 29, 1911 as “the founder, father, creator and since its birth, the directing genius to whose indefatigable energy, determination and resourcefulness is due the marked success achieved by the Telluride Power Company…it will be gratifying to the many old friends of Mr. Nunn in Telluride and vicinity to learn that he has the confidence and support of a two-thirds majority of the board of directors of the Telluride Power Company.”[viii]

Even gossip columns carefully tracked Nunn’s movements, while editorials from every mining district applauded the technological progress that Nunn seemed to typify. Even aside from any possible concurrence of newspaper and business interests, Nunn was apparently lionized both in his day and ours. That the mythology endured long after his death is apparent in a 1977 issue of Colorado Country Life, which states: “L.L. Nunn, whose picture graces our cover this month, was a Very Important Person in his day. His contribution to the electric utility industry was a significant one…We happen to believe that the kind of courage and innovation which Nunn displayed was not untypical of his day, and hopefully of today. Perhaps there are enough Nunn-like individuals around today, willing to endure the criticisms and the skepticism, that the answers will be found to many of our problems – including the energy crisis.”[ix] For a very long time, if still not today, Nunn was remembered the way he wanted to be remembered.

Ultimately, it may not matter what Nunn’s motivations were, or the extent to which consciousness of his own massive legacy influenced his personal dealings. Nunn did contribute to his own public image in ways unavailable to most people. But in his private gifts, as with his public endowments, Nunn may have been acting under the same stimulus: the desire to leave something worthwhile for the future, whether that took the form of the Telluride Association or an elevated, possibly even romanticized, view of himself. A Ouray Herald article of June 16, 1911, titled “Nunn’s Gift Aids Education – Telluride Institute of Electrical Engineering Receives Immense Sum,” notes that “L.L. Nunn has long been known as a practical, unostentatious philanthropist.”[x] Then, as now, the philanthropy seems to matter more than the reasons behind it.

[i] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, Box 7, Folder 24

[ii] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 1.3, Box 2 Folder17

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, Box 6, Folders 31 and 36

[v] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 1.3, Box 2, Folder 20

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 1.3, Box 2, Folder 21

[ix] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Delaney Library, Southwest Periodicals, Dick Easton (ed.), Colorado Country Life, Vol. 25, No. 1, July 1977

[x] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 1.3, Box 2, Folder 7

The

business life vs. the private life of L. L. Nunn, as noted in

his business correspondence at the Center of Southwest Studies:

An evaluation by Christine Ro, Telluride Association Intern at the Center

of Southwest Studies, July-August 2003

For a man surrounded by associates and acquaintances, and so seemingly preoccupied with details of business and industry, Nunn’s letters express a surprising amount of despondency. On March 19, 1895, he writes:

My dear Wrench:

I am going to try to write you a letter but this burning feeling on top of my head suggests a failure, I am very ill. No one believes it but I am really very ill, and I cannot do much and when I try to do a little more than what I can do easily I am completely knocked out. I want to say a word about the way you treat our mutual relation. You continually assume and ascert [sic] that I am changed in feelings toward you, and then you act upon your assumption and change in hundreds of different ways your self, while I am made sensative [sic] to those changes. Just think of the deep insinuation in changing your heading from “My dear Nunn” to “My dear Mr. Nunn.” And yet you do this to me at a time where my entire soul is burdened with the sense of isolation and lonelyness [sic]. Such things turn me faint and often leave me with hardly strength enough to walk. You speak of discontinuing our friendship. Surely this is not the time for you to leave me. I should either be better or dead soon. I have not changed in my feelings toward you. If I am to ill to do as I did formerly I am not to blame, but should have more support not less. I cant write you constantly I have many duties and I cant do much, but I am sure I do as well as I can.[i]

The sense of isolation expressed in this letter recurs in others. Nunn even appears suicidal at times, as when he writes, and appears to identify with, an employee’s suicide:

Marshall Goudy was twenty years old – thoughtful sincere and generous but apparently lonely…I am satisfied that he felt awful oppression which came from a sense of complete isolation and only did what I have so often yearned to do but did not have the courage; perhaps lacked the faith in freedom from the flesh.[ii]

In fostering this isolation, Nunn’s personal relationships were clearly a source of depression. And complicating those relationships may have been his inability to separate his business and personal worlds. (Paul N., in alternately addressing L.L. as “My dear brother” and “Sir,” exemplifies this ambiguity.) Even in letters to A.M. Wrench, for instance, who along with being a director of the San Miguel Consolidated Gold Mining Company, cashier of the First National Bank of Telluride, and Nunn’s partner in real estate and power ventures besides, was perhaps his closest associate, Nunn shifts from business matters to personal issues with odd abruptness. On June 2, 1891 he writes Wrench a stirring, deeply personal letter (“I want to see you and feel so lost without you and still I know I cannot claim you”[iii]), followed four days later by a 7-page account of Gold King financial interests.[iv] Even within that letter, Nunn moves suddenly from reports about business colleagues to professions of affection; did he even conceive of a separation of private and public life?

For not only with Wrench, but with all Nunn’s closest friends, business and companionship were inevitably intertwined. Paul N., his brother, was also chief engineer of the Telluride Power Company, while Nunn numbered among his other good friends Stephen Bailey, his secretary; Malachi Kinney, his business partner in Leadville and Durango; and Cooper Anderson, the superintendent of the Olmsted plant.

It is perhaps not surprising that someone as monumentally busy as Nunn should have combined friends with partners, if for no other reason than convenience. But Nunn’s apparent feelings of betrayal, as with Anderson’s opposition to his educational interests, or abandonment, as with Bailey’s perceived attachment to his job rather than his employer, seem to have stemmed from these dual relationships. Nunn writes on March 30, 1895:

You write as though Bailey was with me. No one is with me. Bailey left me nine days ago. No one wishes to be with one like me…I have absolutely failed every where.[v]

and on April 12, 1895:

Bailey brought Urban here one evening at 8 o’clock and left the next morning at 10. He may have said he wanted to be with me, but he meant that he wished to have me go with him where ever he wished to be in order that he might have the satisfaction of feeling that he was doing a great deal for me and at the same time suffering an inconvenience… my life so far warrants me in saying that I have not an associate who wishes to be with me, or will be with me when not absolutely compelled to be so.[vi]

In this letter, Nunn himself seems to recognize the problems with an employer-employee relationship that doubles as that between friends.

And given the number of associates who were dependent upon him for assistance – the correspondence is full of requests for loans and jobs from strangers as well as old friends – the complications in Nunn’s emotional life become even clearer. “The most difficult part of my life, and that which is bringing me to a premature old age, is dealing with such matters where my intense feeling is being continually wrought upon,”[vii] he writes on December 29, 1898, in speaking of a friend’s appeal for money. As this aspect of Nunn’s life has been relatively neglected for so long, it seems a worthy subject of investigation, one that will help to humanize an often idealized figure.

Even more, insight into Nunn’s personal life may shed light on his business dealings. That is, for someone as technologically and financially sophisticated as he was, Nunn displayed a surprising amount of emotional volatility. It seems as though Nunn’s passions simply changed shape, shifting from the romantic jealousies and dramas that characterized his relationships with the Wrenches and even Bailey toward the educational mission he later operated with similar zeal. Upon Nunn’s break with Wrench, McDermott writes that “henceforward Nunn's emotional impulses would be channeled through the Telluride Institute, which until that point had been largely P. N.’s preserve.”[viii] And just as the Institute seemed to supplant the complications of his emotional attachments, so too did Nunn’s romantic life replace his earlier fervor for religion. Did he just have a fanatical side? It will be interesting to attempt to answer a question like that.

What is certain, however, is that Nunn’s business practices, like his pioneering work with the alternating current or his innovative approach to practical education, were not conventional. Aside from the inevitable consequence of allowing business interests to intrude upon his private life (everything becomes personal, as when business rivals become “conspiracies” to ruin him), Nunn’s customs created new standards for “business” relationships. An October 28, 1902 letter to Cooper Anderson reads:

My association in taking in those who belong to our industries, who have worked loyally for them, may be a little broader than the

ordinary family, in extent, but need not be any the less intense. I have not, nor will I, neglect any personal matter for business, except as my

judgment informs me that the business is of more importance intrinsically than the other. It is merely, with me, a matter of degree.[ix]

As in so many other fields, Nunn here is an original. His commitment to companionship, to loyalty, and to the needs of those closest to him, even at the potential expense of business interests, marks him out as unusual among people with business concerns as far-reaching as his. “Will we soon begin to tire of the grind of business…?” he asks James Campbell in a 1900 Christmas letter.[x] The implication seems to be that business was never Nunn’s priority.

[i] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, Box 7, Folder 24

[ii] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, , Box 24, Folder 23

[iii] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, , Box 1, Folder 50

[iv] Ibid

[v] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, , Box 7, Folder 24

[vi] Ibid

[vii] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, , Box 12, Folder 17

[viii] (McDermott, Scott, introduction to) Bailey, Stephen A., LL Nunn: A Memoir, Telluride Association, 1993, page xi

[ix] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, , Box 23, Folder 11

[x] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, , Box 17, Folder 6

Public

service and business success of L. L. Nunn –

mutually exclusive?

An evaluation by Christine Ro, Telluride Association Intern at the

Center of Southwest Studies, July-August 2003

The conflict between Nunn’s business and philanthropic interests seems to echo the tension between his working and personal worlds. In retrospect, the separation of the Telluride Power Company’s educational and commercial work appears inevitable. The WCPC records are especially useful in elucidating this kind of matter – in attempting to trace the events that led to this break.

The correspondence reveals a worsening of financial conditions starting about 1895 or 1896; with lawsuits accumulating, notices of unpaid bills increasing, silver prices fluctuating, and pressure to sell various stock and, eventually, the First National Bank of Telluride, growing, Nunn’s financial situation increasingly becomes a source of anxiety to Nunn as well as his associates. “Gold King matters are in the worst possible condition,” he writes to P.N. on May 18, 1897[i]; on April 23: “The future is dark…I do not know what the future has for me.”[ii] Nunn also notes that the year “has been one of unnecessary anxiety and failure. The interests of my companies as well as my own have been unprotected and in many instances fallen a prey to the pirates of this district, where situated.”[iii]

And the situation undeniably affects his personal life. Nunn, first of all, exhibits more of the insecurity and self-doubt that perhaps always existed in his character. A letter from A.M. Wrench on August 22, 1897, notes: “It is most unfortunate that the pipe line has proven so defective, and I realize fully how serious a matter it is, but I fail to see how you can consider it in any way your failure.”[iv] Nunn’s financial troubles only exacerbate his nagging sense of inadequacy. They also aggravate, in characteristic psychosomatic fashion, Nunn’s health; he writes on September 6, 1897, “I have suffered so much from my nerves the past month that my own matters have been neglected.”[v]

Importantly, Nunn’s deteriorating economic situation also intensifies the divisions between him and his closest associates. In responding to his brother’s account of financial woes, for examples, while feeling himself to be blamed, Paul N. writes a letter that he himself acknowledges as “nasty.” More serious than the brothers’ tensions are the perceived betrayals of close associates during this time; Nunn describes in multiple letters the “treachery” of William Story and W.B. Slick, as well as the “malice” of other colleagues.[vi]

Solutions to the financial crisis are proposed, while P.N. optimistically reimagines the company’s work habits in February 12, 1896 letter:

I cannot undertake to answer your most

important letter, -- most important for a long time, because it looks to the

remedying of those defects which are lacking from our successes and lives

most -- of that which gives life its dignity.

I can’t answer! I can

only make some observations, -- results of many hours thought both before

and since the receipt of yours. We must have opportunity to talk, and

talk when not tired and relaxed.

I can see four sources of failure- Procrastination-

Indecision-

Lack of System

Overwork, or inalertness

Procrastination, -- not in not doing enough, but in postponing disagreeable

tasks, and more especially in not selecting, each day, the most important

even though they be obscure, instead of taking up those which float along to

us first, and force themselves upon our attention. In other words, there is

too much “Out of sight, out of mind.”

Indecision needs no explanation. Logan

has suffered much, is now suffering from indecision as 5000 or 1000 volt

distribution. Yet there is

generally some small gain in this. We shall probably use part of

each. Except for indecision, Logan ought to have been running by Jan. 1.

Lack of System, is interwoven with indecision.

The best work I could have done (best all of us could have done) for

the first three weeks of this scheme, would have been to plan and decide;

form a complete way of doing each particular thing, then set

ourselves to list every item, no matter how small, required, and have each

provided for at proper time. Then

we would not have suffered disappointment as to cost of this work.

Labor and supplies listed in my estimate, have cost less rather than

more. The additional cost lies

in what I omitted, and in simple delays, all avoidable.

System will provide things when needed, at least cost, and with less effort,

around emergencies. Emergencies take money.

Overwork, not always from too long hours or too hard application, but from

being in a “muddle,” from pulling when things seem to drag, from

intermittently caused by interruptions etc.

We float when we should steer, we discuss and try to decide,

when too weary to perceive clearly, and do our work, to do it over again.

Regularity would remedy lots of this, and in spite of Keely’s statement

that regularity leads to nervous exhaustion, I believe it is the way to

accomplish. Emily says “why get ready?

It is wasted time! Why

not do it.” It is not

a successful way for me. There is another thing. We do not check up results

carefully enough. We start

people to doing things, and take their results, without watching their work,

and directing etc. as we should. I

do at least.

Last of all, and perhaps all in all, it comes back to this one principle; control,--

self control, and control of others under our directions.[vii]

Others blame Nunn’s philanthropic work. Wrench writes,

We have been unfortunate the last few years…It has seemed to me many times that we have been guided in business matters more by the heart, than by good Common Sense…We have been bled from first one side, then another, have given up to this thing, and that, helped this man or woman until we have found ourselves in debt, our property depreciated in value, and our income cut down to almost nothing.

He holds Nunn’s generosity to be in excess:

The remedy seems to me to be ours for the using, viz. a stricter attention to our own affairs, leaving others to look for themselves, until such time as we may be able to again be that assistance to others, which is so pleasant a thing for both of us. And especially so to you.[viii]

In a September 14, 1908 letter, Nunn responds heatedly to a similar sentiment, expressed more bluntly by James Campbell:

Your billingsgate language and accusations of dishonesty, such as the company’s “contributions” to your charities or your philanthropy,” “the funds diverted,” the “lack of ‘business principles,’” “I want to see this property run on business principles rather than for the benefit of friends and favorites,” “the business being run in the ‘interests of the Institute and friends,’” without even a pretence of supporting them by evidence and contrary to every evidence, are improper if not criminal, and must not continue.[ix]

Whether a scapegoat or the genuine cause, Nunn’s philanthropic commitments are at least partially blamed for the financial losses, which continue in cycles until his departure from the company. Given the enormous difficulties of reconciling public service with business commitments, Nunn’s achievements in the former seem all the more remarkable.

[i] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, Box 11 Folder 23

[ii] Ibid

[iii] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, Box 11, Folder 19

[iv] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, Box 11, Folder 17

[v] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, Box 11, Folder 23

[vi] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, Box 11, Folders 17 and 23

[vii] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, Box 9, Folder 9

[viii] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, Box 11, Folder 17

[ix] Center of Southwest Studies – Fort Lewis College, Western Colorado Power Company Collection M002, Series 2.1, Box 26, Folder 19

A

bibliography of L. L. Nunn materials at the Center of

Southwest Studies:

Compiled

by Christine Ro, Telluride Association Intern at the Center of Southwest

Studies, July-August 2003

Books:

Bailey, Stephen A.

LL Nunn -- A Memoir

published by Telluride Association, 1933

definitive Nunn biography – excerpts many primary

sources and covers every period of Nunn’s life but lacks thoroughness or

impartiality (written by Nunn’s secretary and commissioned and published under

the auspices of the Telluride Association)

SW Special Collections M002

Clark, Denis E. (compiler)

Telluride Power: A Brief Illustrated History of the Early Days

published by the Telluride Association History Committee, 2001

“This brief history covers the early development of LL Nunn’s hydroelectric business and the educational enterprises that went along with them.” – includes a timeline, maps, and many photographs

SW Special Collections M002

Cummins, Mrs. M.L.

“An Industry and an Institution of Higher Learning are Born at Ames, Colorado – 1891”

pages 130-4 in Pioneers of the San Juan Country, 1961, Volume IV

published by Big Mountain Press for Sarah Platt Decker Chapter, N.S.D.A.R. (Denver)

discusses the installation of the Ames plant and the beginnings of the Telluride Association

SW F782 S19 D35 v. 1-4

also F782.S19 D35 v. 1-4 c. 2 (in Reed Library of Fort Lewis College)

SW F782.S19 D35 v. 3 c. 3

SW F782.S19 D35 v. 3-4 c.2

Fetter, Richard L. and Suzanne

Telluride: From Pick to Powder

published by the Caxton Printers (Caldwell, Idaho), 1979

lightweight, entertaining history of Telluride, from the 1870s to 1970s – Nunn is represented as integral to the town’s development

SW F784 .T4 F47 1979

Marshall, John B.

“The Story of J.A. Porter”

pages 76-86 in Pioneers of the San Juan Country, 1952, Volume III

published by Big Mountain Press for Sarah Platt Decker Chapter, N.S.D.A.R. (Denver)

short biography of mine manager John A. Porter briefly mentions Nunn’s provision of power to San Juan mines

SW F782 S19 D35 v. 1-4

also F782.S19 D35 v. 1-4 c. 2 (in Reed Library of Fort Lewis College)

SW F782.S19 D35 v. 3 c. 3

SW F782.S19 D35 v. 3-4 c.2

Mott, Mary Kirker

“At Lake City and Telluride”

pages 87-100 in Pioneers of the San Juan Country, 1946, Volume II

published by Big Mountain Press for Sarah Platt Decker Chapter, N.S.D.A.R. (Denver)

Telluride resident reminisces about her experiences in the area, from 1870s to 1890s – Nunn is briefly mentioned in connection with the Telluride Power Company

SW F782 S19 D35 v. 1-4

also F782.S19 D35 v. 1-4 c. 2 (in Reed Library of Fort Lewis College)

Rathmell, Ruth

Of Record and Reminiscence – Ouray and Silverton

published by North Suburban Printing & Publishing, Inc., 1976 (Westminster, Colorado)

good photos

SW F784 O 82 R3

Sweeting, Orville J.

Telluride: Power for the Intermountain West: A History of the Telluride Power Company, Predecessor of the Utah Power and Light Company

manuscript microfilm, 395 pages

unpublished manuscript, completed January 1975

final revision (ribbon copy of final manuscript) of The

Education Experiment of L.L.

comprehensive history of Nunn’s life and developments in mining, power, and education, with many excerpted letters and other primary sources

SW Center Microforms Coll I 063

Weber, Rose

A Quick History of Telluride

published by Little London Press, 1974 (Colorado Springs)

thin volume of mining-era reminiscences, with great photographs – includes account of Nunn’s electrical developments

SW F784 T4 W4

Wenger, Martin G.

Recollections of Telluride, 1895-1920

published by Basin Reproduction & Printing Company, 1978 (Durango, Colorado)

thin volume of mining-era reminiscences, with great photographs – includes account of Nunn’s electrical developments

SW F784 T4 W42

Pamphlets:

“A History – Utah Power & Light Company,” 21 pages

published by the Utah Power & Light Company, circa 1986

same Nunn-related content as “Utah Power & Light Company”

SW Special Collections M002 RG1 S1.2 Box1 Folder19

“A Romance of Electricity on the Western Slope,” 21 pages

published by the Western Colorado Power Company, 1968

illustrated volume charting the history of the WCPC, – mentions Nunn’s innovations with the alternating current (republished version of “The First 50 Years: A Romance of Electricity on the Western Slope” – content unchanged)

SW HD 9685 R65

also SW Special Collections M002 RG1 S1.2 Box1 Folder14

“Power for the People,” 16 pages

published by the Utah Power & Light Company, 1969

booklet that “attempts to describe the scene behind the switch at Utah Power & Light Company” briefly mentions, under the heading “The Coming of Electricity,” Nunn’s innovation with the alternating current

SW Special Collections M002 RG1 S1.2 Box1 Folder 15

“The First 50 Years: A Romance of Electricity on the Western Slope,” 16 pages

published by the Western Colorado Power Company, 1963

illustrated volume charting the history of the WCPC – mentions Nunn’s innovations with the alternating current

SW Special Collections M002 RG1 S1.2 Box1 Folder 10

“Utah Power & Light Company,” 14 pages

published by the Utah Power & Light Company, circa 1962

in the context of its own history of electrification, explores Nunn’s involvement in the mining districts, the success of the alternating current at Ames, and the Telluride education program

SW Special Collections M002 RG1 S1.2 Box1 Folder 9

Periodicals:

Alder, Douglas D.

“The Ghost of Mercur”

pages 33-42 in Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol.29, 1961

published by the Utah State Historical Society

discusses the unique nature of the Mercur mine and its centrality of electricity to mining operations there – Nunn is briefly mentioned as the provider of electricity to the Golden Gate Mill

SW Periodicals

Britton, Charles C.

“An Early Electric Power Facility in Colorado”

pages 185-95 in Colorado Magazine, Vol.49, No.3, Summer 1972

published by The State Historical Society of Colorado

explores the growth of the Telluride power system, particularly the developments at the Gold King Mine

SW Periodicals

Buys, Christian J.

“Power in the Mountains: Lucien Nunn Catapults the San Juans into the Age of Electricity”

pages 25-37 in Colorado Heritage, Issue 4, 1986

published by the State Historical Society of Colorado

summary of Nunn’s technological achievements – offers little in the way of new information but provides a good introduction to his power developments – draws heavily on the Bailey biography and offers the same favorable account

SW Periodicals

Easton, Dick (ed.)

“That Good Ol’ American Ingenuity”

pages 4-5 in Colorado Country Life, Vol.25, No.1, July 1977

published by the Colorado Rural Electric Association

short article about the alternating current excerpts “A Romance of Electricity on the Western Slope” (see under Pamphlets)

SW Periodicals

Haycock, Obed C.

“Electric Power Comes to Utah”

pages 173-87 in Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol.45, No.2, Spring 1977

published by the Utah State Historical Society

“This article will describe the growth of electric power – primarily before the formation of Utah Power and Light Company – and the contributions of the Nunn brothers and others to the state’s development.” – summarizes the origins of electric power in Utah, up to the formation of the Utah Power & Light Company in 1912 – discusses the Grace, Olmsted, Ames and Nunns plants

SW Periodicals

McCormick, John S.

“The Beginning of Modern Electric Power Service in Utah, 1912-22”

pages 4-22 in Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol.56, No.1, Winter 1988

published by the Utah State Historical Society

explores the advent of electricity in Utah from the formation of the Utah Power & Light Company – Nunn and the Telluride Power Company are mentioned briefly in connection with the UP&L’s acquisition of electric power companies

SW Periodicals

Topping, Gary (ed.)

“An Adventure for Adventure’s Sake Recounted by Robert B. Aird”

from Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol.62, No.3, Summer 1994

published by the Utah State Historical Society

the author very briefly mentions visiting some Nunn-related sites during a trip to Telluride

SW Periodicals

This report was produced by Christine Ro, Telluride Association Intern at the Center of Southwest Studies, July-August 2003. Editorial assistance by Todd Ellison in August of 2003 and in April/ July of 2004.

Doing your own research: This description of a portion of one of the collections at the Fort Lewis College Center of Southwest Studies is provided to inform interested parties about the nature and depth of the repository's collections. It cannot serve as a substitute for a visit to the repository for those with substantial research interests in the collections.

These collections are located at the Center of Southwest Studies on the campus of Fort Lewis College. Interested researchers should phone the archivist at 970/247-7126 or send electronic mail to the archivist at: Ellison_T@fortlewis.edu . Click here to use our E-mail Reference Request Form. The Center does not have a budget for outgoing long-distance phone calls to answer reference requests, so if you do not provide an email address for our response you will need to be willing to accept a collect call from the Center.